If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

If you could put a replica of this statue anywhere in a Minneapolis park, where would you put it?

One of the most intriguing “might-have-beens” in Minneapolis park history was the proposed construction of a Japanese Temple on an island in Lake of the Isles. (If you missed it, read the story of John Bradstreet’s proposal.) But that was not the only proposal to spruce up an island in a Minneapolis park.

On March 15, 1961 the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners approved the placement of a replica of the Statue of Liberty on an island in another body of water.

Park board proceedings attribute the proposal to a Mr. Iner Johnson. He offered to donate and install the 10-foot tall replica statue made of copper and the park board accepted the offer — as long as the park board would incur no expense.

I can find no further information on the proposal or why the plan was never executed — or if it was, what happened to the statue.

The intended location of the statue was the island in … Powderhorn Lake.

Island in Powderhorn Lake from the southeast shore, near the rec center in 2012. The willow gives the impression of an entrance to a green cave. (David C. Smith)

The Minneapolis Morning Tribune of March 16, 1961 reported that Lady Liberty was to be installed for the Aquatennial that summer. Was it? Does anyone remember it? I’ve never seen a picture or read a description.

Another park feature from H.W.S. Cleveland

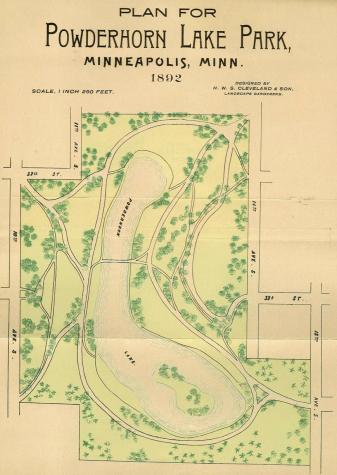

The man-made island was first proposed in the plan created for Powderhorn Park in 1892 by H. W. S. Cleveland and Son. It is the only Minneapolis park plan that carried that attribution. Horace Cleveland’s son, Ralph, who had been the superintendent of Lakewood Cemetery since 1884, joined his father’s business in 1891 according to a note in Garden and Forest (July 1, 1891).

More on Garden and Forest. Horace Cleveland contributed frequently to the influential weekly horticulture and landscape art magazine through his letters to the editor, Charles Sprague Sargent. Sargent was also the first director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. Click on Garden and Forest to learn more about the magazine and its searchable archive. (Thank you, Library of Congress.)

Cleveland’s plan for Powderhorn Park featured a bridge over the lake, about where the north shore is now, and an island. The plan was published in the park board’s 1892 annual report. (Horace W. S. Cleveland, MPRB)

Horace Cleveland was 78 and finding the field work of landscape architecture physically challenging when he and Ralph joined forces to produce a plan for Powderhorn. Only a year later his doctor prohibited him from working further. The Cleveland’s were paid $546 for their work at Powderhorn, but the park board didn’t implement parts of the plan for more than ten years.

Horace Cleveland had been a strong booster for making the lake and surrounding land into a park. Powderhorn Lake had been considered for acquisition as a park from the earliest days of the park board in 1883. However, the park board believed landowners in the vicinity of the lake were asking far too high a price for their land. To learn more of the park’s creation see the park board’s history of Powderhorn Park.

After I wrote that history, I found a transcript of a letter Cleveland had written to the park board (Minneapolis Tribune, July 26, 1885) encouraging the board to acquire about 150 acres from Lake Street to 35th Street between Bloomington and Yale avenues, which was, Cleveland claimed, the watershed for Powderhorn Lake. (I can find no Yale Avenue on maps of that time. Does anyone know what was once Yale Avenue?)

The letter repeated Cleveland’s frequent message about acquiring land for parks before it was developed or became prohibitively expensive. But he also claimed that due to the unique topography around the lake that if it were allowed to be developed it would become a nuisance that would be very costly to clean up.

I’ll quote a couple highlights from his argument for the acquisition of Powderhorn Lake and Park:

I am so deeply impressed with the value and importance of one section…I am impelled to lay before you the reasons …that you will very bitterly regret your failure to secure it if you suffer the present opportunity to escape.

The surrounding region is generally very level and the lake is sunk so deep below this average surface, that its presence is not suspected till the visitor looks down upon it from its abrupt and beautifully rounded banks. The water is pure and transparent and thirty feet deep, and its shape (from which it derives its name) is such as to afford the most favorable opportunity for picturesque development by tasteful planting of its banks…All the most costly work of park construction has already been done by nature.

Cleveland concluded his letter to the park board by writing,

I feel it my duty in return for the bounty you have done in employing me as your professional advisor, to lay before you this statement of my own convictions, and request, in justice to myself, that it may be placed on your records, whatever may be your decision.

On the day Cleveland’s letter was presented to the park board, the board voted not to acquire Powderhorn Lake as a park and Cleveland’s letter was not printed in the proceedings of the park board either. Still the lake and surrounding land—about 60 acres, or 40 percent of what Cleveland had initially recommended—were acquired in 1890-1891 and Cleveland was hired to create a design for the park. Cleveland’s proposed foot bridge over the narrow neck of the lake was not built, even though Theodore Wirth incorporated Cleveland’s bridge into his own plan presented in 1907. However Cleveland’s island was created in the lake in the ensuing years.

In a recap of park work in 1893, park board president Charles Loring noted in his annual report that a “substantial dredge boat was built and equipped and is ready to work” at Powderhorn Lake. “I hope the board will be able to make an appropriation large enough,” he continued, “to keep the apparatus employed all of the next season.”

Loring’s hope was really more of a wish because the depression of 1893 was already having drastic consequences for the Minneapolis economy, property tax revenues and park board budgets. Despite severe cutbacks in spending in 1894, however, the park board devoted about 20% of its $48,000 improvement budget to Powderhorn. Park superintendent William Berry reported that the dredge was active in the lake for 90 days. The result was about 1.7 new acres of land created by dredging and filling along the lake’s marshy shore. In addition, nearly 15,000 cubic yards of earth were moved from near 10th Avenue to fill low areas on the north end of the lake.

An island emerges

The next year, 1895, the island was finally created. The park board spent $10,000, one-third of its dwindling improvement budget, dredging the lake and creating the island. Another 7.3 acres of dry land were created along the lake shore and an island measuring just over one-half acre was created in the southern end of the lake.

An island being created by a dredge in Powderhorn Lake, 1895. Tram tracks were built on a pontoon bridge to carry the dredged material. The photo appeared in the 1895 annual report of the park board. Not a lot of trees around at the time. (Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board)

By 1897, the only activity at Powderhorn covered in the annual report was the “raising of the dredge boat,” which had sunk that spring, and watering trees and mowing lawns in the “finished portion” of the park. Two years later, Berry reported that the west side of the park was graded, another nine acres of lawn were seeded and 100 trees and 1600 shrubs were planted to a plan created by noted landscape architect Warren Manning. Horace Cleveland had left Minneapolis in 1896, moving with his son to Chicago, where he died in 1900.

It’s unlikely, due to his age, that Cleveland played any role in the actual creation of the island in Powderhorn Lake in 1895. And credit for the idea of an island may not be due solely to Cleveland either, but also to a coincidence in the creation of Loring (Central) Park in 1884. Cleveland’s original plan for Loring Park did not include an island in the pond then known as Johnson’s Lake. Charles Loring later told the story in his diary entry of June 12, 1884 (Charles Loring Scrapbooks, Minnesota Historical Society),

“In grading the lake in Central [Loring] Park the workmen left a piece in the center which I stopped them from taking out. I wrote Mr. Cleveland that I should be pleased to leave it for a small island. He replied that it would be alright. I only wish I had thought of it earlier so as to have had a larger island.”

The development of the island envisioned by Loring while supervising construction, then approved by Cleveland, proved to be a famous success. (The island no longer exists.) Four years later, on October 3, 1888, Garden and Forest published an article about Central (Loring) Park and concluded a glowing tribute with these words:

When it is considered that artificial lakes and islands are always counted difficult of construction if they are to be invested with any charm of naturalness, the success of this attempt will not be questioned, while the rapidity with which the artist’s idea has grown into an interesting picture is certainly unusual. The park was designed by Mr. H.W.S. Cleveland.

Given such praise, it is not surprising that Cleveland would be willing to try an island from the beginning in Powderhorn Lake. Between the time it was proposed by Cleveland and actually created three years later, decorative islands had also earned a faddish following on the heels of Frederick Law Olmsted’s highly praised island and shore plantings on the grounds of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. One landscape historian wondered whether Olmsted’s creation and treatment of his island in Chicago could have been influenced by his 1886 visit to Minneapolis where he would have seen Loring and Cleveland’s island in Loring Park.

The success of islands in Loring Pond and Powderhorn Lake likely also influenced Theodore Wirth when he proposed creating islands in Lake Nokomis and Lake Hiawatha. Both of those islands were scratched from final plans.

The island in Powderhorn Lake is one of three islands that remain in Minneapolis lakes—and the only one that was man-made. Only two of the four original islands in Lake of the Isles still exist. The two long-gone islands were incorporated into the southwestern shore of the lake when it was dredged and reshaped from 1907 to 1910. The two islands that remain were significantly augmented by fill during that period.

A handful of islands still exist in the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, although many more were flooded when the Ford Dam was built. Another augmented island—Hall’s Island—may be re-created in the near future as part of the RiverFIRST plan for the Scherer site upstream from the Plymouth Avenue bridge.

Although Horace Cleveland died in 1900, when the Minneapolis economy finally boomed again the park board voted in April 1903 to dust off and implement the rest of the 1892 Powderhorn Lake Park plan of H.W.S. Cleveland and Son.

The lake was reduced by about a third in 1925 when the northern arm of the lake was filled. Theodore Wirth, the park superintendent at the time, contended that the lake level had dropped six feet for unknown reasons after his arrival in 1906. The filled portion of the lake was converted into ball fields — a use of park land that was unheard of in Horace Cleveland’s time. The lake that Cleveland estimated at 30 to 40 acres in 1885, when he recommended its acquisition as a park, is now only a little over 11 acres.

The northern arm of Powderhorn Lake was filled in 1925. I wonder if the folks who lived in the apartments on Powderhorn Terrace had their rent reduced when they no longer had lakeshore addresses? (City of Parks, MPRB)

Now about that Statue of Liberty. Does anyone remember it in Powderhorn Lake?

David C. Smith

© David C. Smith